Percival Lowell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Percival Lowell (; March 13, 1855 – November 12, 1916) was an American businessman, author, mathematician, and

Percival Lowell was born on March 13, 1855, in

Percival Lowell was born on March 13, 1855, in

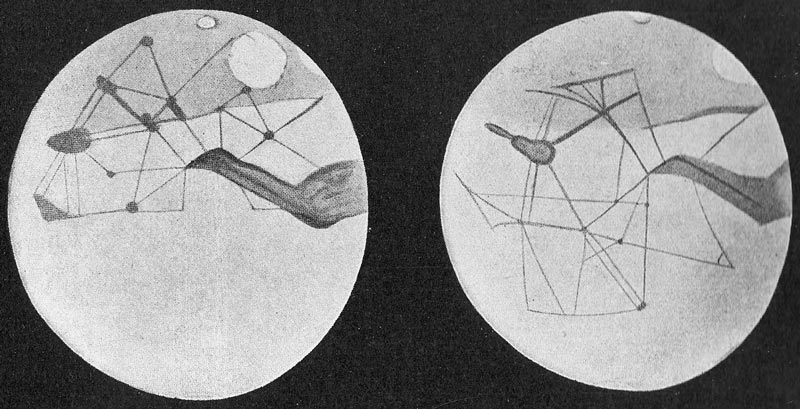

For some fifteen years (1893 to about 1908) Lowell studied Mars extensively, making intricate drawings of the surface markings as he perceived them. Lowell published his views in three books: ''Mars'' (1895), ''Mars and Its Canals'' (1906), and ''Mars As the Abode of Life'' (1908). With these writings, Lowell more than anyone else popularized the long-held belief that these markings showed that Mars sustained intelligent life forms.

His works include a detailed description of what he termed the "non-natural features" of the planet's surface, including especially a full account of the "canals," single and double; the "oases," as he termed the dark spots at their intersections; and the varying visibility of both, depending partly on the Martian seasons. He theorized that an advanced but desperate culture had built the canals to tap Mars' polar ice caps, the last source of water on an inexorably drying planet.

For some fifteen years (1893 to about 1908) Lowell studied Mars extensively, making intricate drawings of the surface markings as he perceived them. Lowell published his views in three books: ''Mars'' (1895), ''Mars and Its Canals'' (1906), and ''Mars As the Abode of Life'' (1908). With these writings, Lowell more than anyone else popularized the long-held belief that these markings showed that Mars sustained intelligent life forms.

His works include a detailed description of what he termed the "non-natural features" of the planet's surface, including especially a full account of the "canals," single and double; the "oases," as he termed the dark spots at their intersections; and the varying visibility of both, depending partly on the Martian seasons. He theorized that an advanced but desperate culture had built the canals to tap Mars' polar ice caps, the last source of water on an inexorably drying planet.

While this idea excited the public, the astronomical community was skeptical. Many astronomers could not see these markings, and few believed that they were as extensive as Lowell claimed. As a result, Lowell and his observatory were largely ostracized. Although the consensus was that some actual features did exist which would account for these markings, in 1909 the sixty-inch

While this idea excited the public, the astronomical community was skeptical. Many astronomers could not see these markings, and few believed that they were as extensive as Lowell claimed. As a result, Lowell and his observatory were largely ostracized. Although the consensus was that some actual features did exist which would account for these markings, in 1909 the sixty-inch

Although Lowell was better known for his observations of Mars, he also drew maps of the planet

Although Lowell was better known for his observations of Mars, he also drew maps of the planet

Although Lowell's theories of the Martian canals, of surface features on Venus, and of Planet X are now discredited, his practice of building observatories at the position where they would best function has been adopted as a principle. He also established the program and setting which made the discovery of Pluto by

Although Lowell's theories of the Martian canals, of surface features on Venus, and of Planet X are now discredited, his practice of building observatories at the position where they would best function has been adopted as a principle. He also established the program and setting which made the discovery of Pluto by

astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, natural satellite, moons, comets and galaxy, g ...

who fueled speculation that there were canals

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or river engineering, engineered channel (geography), channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport watercraft, vehicles (e.g. ...

on Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury (planet), Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Mars (mythology), Roman god of war. Mars is a terr ...

, and furthered theories of a ninth planet within the Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar S ...

. He founded the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona

Flagstaff ( ) is a city in, and the county seat of, Coconino County, Arizona, Coconino County in northern Arizona, in the southwestern United States. In 2019, the city's estimated population was 75,038. Flagstaff's combined metropolitan area has ...

, and formed the beginning of the effort that led to the discovery of Pluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the Sun. It is the largest ...

14 years after his death.

Life and career

Early life and work

Percival Lowell was born on March 13, 1855, in

Percival Lowell was born on March 13, 1855, in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, the first son of Augustus Lowell

Augustus Lowell (January 15, 1830 – June 22, 1900) was a wealthy Massachusetts industrialist, philanthropist, horticulturist, and civic leader. A member of the Brahmin Lowell family, he was born in Boston to John Amory Lowell and his secon ...

and Katherine Bigelow Lowell. A member of the Brahmin

Brahmin (; sa, ब्राह्मण, brāhmaṇa) is a varna as well as a caste within Hindu society. The Brahmins are designated as the priestly class as they serve as priests (purohit, pandit, or pujari) and religious teachers (guru ...

Lowell family

The Lowell family is one of the Boston Brahmin families of New England, known for both intellectual and commercial achievements.

The family had emigrated to Boston from England in 1639, led by the patriarch Percival Lowle (1571–1665). The surn ...

, his siblings included the poet Amy Lowell

Amy Lawrence Lowell (February 9, 1874 – May 12, 1925) was an American poet of the imagist school, which promoted a return to classical values. She posthumously won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1926.

Life

Amy Lowell was born on Febru ...

, the educator and legal scholar Abbott Lawrence Lowell

Abbott Lawrence Lowell (December 13, 1856 – January 6, 1943) was an American educator and legal scholar. He was President of Harvard University from 1909 to 1933.

With an "aristocratic sense of mission and self-certainty," Lowell cut a large f ...

, and Elizabeth Lowell Putnam

Elizabeth Lowell Putnam (2 February 1862–1935) was an American philanthropist and an activist for prenatal care. She was born (as Bessie Lowell) in Boston, Massachusetts, the daughter of Augustus Lowell and Katherine Bigelow Lowell. A member o ...

, an early activist for prenatal care. They were the great-grandchildren of John Lowell

John Lowell (June 17, 1743 – May 6, 1802) was a delegate to the Congress of the Confederation, a Judge of the Court of Appeals in Cases of Capture under the Articles of Confederation, a United States district judge of the United States Distr ...

and, on their mother's side, the grandchildren of Abbott Lawrence

Abbott Lawrence (December 16, 1792, Groton, Massachusetts – August 18, 1855) was a prominent American businessman, politician, and philanthropist. He was among the group of industrialists that founded a settlement on the Merrimack River that ...

.

Percival graduated from the Noble and Greenough School

The Noble and Greenough School, commonly known as Nobles, is a coeducational, nonsectarian day and five-day boarding school for students in grades seven through twelve. It is near Boston on a campus that borders the Charles River in Dedham, Massa ...

in 1872 and Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

in 1876 with distinction in mathematics. While at Harvard he joined Delta Kappa Epsilon

Delta Kappa Epsilon (), commonly known as ''DKE'' or ''Deke'', is one of the oldest fraternities in the United States, with fifty-six active chapters and five active colonies across North America. It was founded at Yale College in 1844 by fifteen ...

fraternity. At his college graduation, he gave a speech, considered very advanced for its time, on the nebular hypothesis

The nebular hypothesis is the most widely accepted model in the field of cosmogony to explain the formation and evolution of the Solar System (as well as other planetary systems). It suggests the Solar System is formed from gas and dust orbitin ...

. He was later awarded honorary degrees from Amherst College

Amherst College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts. Founded in 1821 as an attempt to relocate Williams College by its then-president Zephaniah Swift Moore, Amherst is the third oldest institution of higher educatio ...

and Clark University

Clark University is a private research university in Worcester, Massachusetts. Founded in 1887 with a large endowment from its namesake Jonas Gilman Clark, a prominent businessman, Clark was one of the first modern research universities in the ...

. After graduation he ran a cotton mill

A cotton mill is a building that houses spinning (textiles), spinning or weaving machinery for the production of yarn or cloth from cotton, an important product during the Industrial Revolution in the development of the factory system.

Althou ...

for six years.

In the 1880s, Lowell traveled extensively in the Far East. In August 1883, he served as a foreign secretary and counselor for a special Korean

Korean may refer to:

People and culture

* Koreans, ethnic group originating in the Korean Peninsula

* Korean cuisine

* Korean culture

* Korean language

**Korean alphabet, known as Hangul or Chosŏn'gŭl

**Korean dialects and the Jeju language

** ...

diplomatic mission to the United States. He lived in Korea for about two months. He also spent significant periods of time in Japan, writing books on Japanese religion, psychology, and behavior. His texts are filled with observations and academic discussions of various aspects of Japanese life, including language, religious practices, economics, travel in Japan, and the development of personality.

Books by Lowell on the Orient include ''Noto: An Unexplored Corner of Japan'' (1891) and ''Occult Japan, or the Way of the Gods'' (1894), the latter from his third and final trip to the region. His time in Korea inspired ''Chosön: The Land of the Morning Calm'' (1886, Boston). The most popular of Lowell's books on the Orient, ''The Soul of the Far East'' (1888), contains an early synthesis of some of his ideas that, in essence, postulated that human progress is a function of the qualities of individuality and imagination. The writer Lafcadio Hearn called it a "colossal, splendid, godlike book."Leonard, Louise. ''Percival Lowell: An Afterglow''. RG Badger, 1921, pp. 33, 46. At his death he left with his assistant Wrexie Leonard an unpublished manuscript of a book entitled ''Peaks and Plateaux in the Effect on Tree Life''.

Lowell was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and ...

in 1892. He moved back to the United States in 1893. He became determined to study Mars and astronomy as a full-time career after reading Camille Flammarion

Nicolas Camille Flammarion FRAS (; 26 February 1842 – 3 June 1925) was a French astronomer and author. He was a prolific author of more than fifty titles, including popular science works about astronomy, several notable early science fic ...

's ''La planète Mars''. He was particularly interested in the canals of Mars, as drawn by Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli

Giovanni Virginio Schiaparelli ( , also , ; 14 March 1835 – 4 July 1910) was an Italian astronomer and science historian.

Biography

He studied at the University of Turin, graduating in 1854, and later did research at Berlin Observatory, ...

, who was director of the Milan Observatory. The Boston geologist George Russel Agassiz noted that Lowell made the decision to begin his observations after hearing that Schiaparelli began to experience failing eyesight. Beginning in the winter of 1893–94, using his wealth and influence, Lowell dedicated himself to the study of astronomy, founding the observatory which bears his name. He chose Flagstaff, Arizona Territory, as the home of his new observatory. At an altitude of over , with few cloudy nights, and far from city lights, Flagstaff was an excellent site for astronomical observations. This marked the first time an observatory had been deliberately located in a remote, elevated place for optimal seeing which included enhanced image quality, sharpness and steadiness. At his Flagstaff observatory Lowell favored the use of smaller telescopes rather than larger ones, believing that they were usually better for viewing fine planetary details. He was assisted in setting up his observatory by William Pickering, another observer of Mars who had noted the lines seen by Schiaparelli as well.

In 1904, Lowell received the Prix Jules Janssen, the highest award of the Société astronomique de France, the French astronomical society. For the last 23 years of his life, astronomy, Lowell Observatory, and his and others' work at his observatory were the focal points of his life.

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

very much saddened Lowell, a dedicated pacifist. This, along with some setbacks in his astronomical work (described below), undermined his health and contributed to his death from a stroke on November 12, 1916, aged 61. Lowell is buried on Mars Hill near his observatory. Lowell claimed to "stick to the church" though at least one current author describes him as an agnostic.

Canals of Mars

For some fifteen years (1893 to about 1908) Lowell studied Mars extensively, making intricate drawings of the surface markings as he perceived them. Lowell published his views in three books: ''Mars'' (1895), ''Mars and Its Canals'' (1906), and ''Mars As the Abode of Life'' (1908). With these writings, Lowell more than anyone else popularized the long-held belief that these markings showed that Mars sustained intelligent life forms.

His works include a detailed description of what he termed the "non-natural features" of the planet's surface, including especially a full account of the "canals," single and double; the "oases," as he termed the dark spots at their intersections; and the varying visibility of both, depending partly on the Martian seasons. He theorized that an advanced but desperate culture had built the canals to tap Mars' polar ice caps, the last source of water on an inexorably drying planet.

For some fifteen years (1893 to about 1908) Lowell studied Mars extensively, making intricate drawings of the surface markings as he perceived them. Lowell published his views in three books: ''Mars'' (1895), ''Mars and Its Canals'' (1906), and ''Mars As the Abode of Life'' (1908). With these writings, Lowell more than anyone else popularized the long-held belief that these markings showed that Mars sustained intelligent life forms.

His works include a detailed description of what he termed the "non-natural features" of the planet's surface, including especially a full account of the "canals," single and double; the "oases," as he termed the dark spots at their intersections; and the varying visibility of both, depending partly on the Martian seasons. He theorized that an advanced but desperate culture had built the canals to tap Mars' polar ice caps, the last source of water on an inexorably drying planet.

While this idea excited the public, the astronomical community was skeptical. Many astronomers could not see these markings, and few believed that they were as extensive as Lowell claimed. As a result, Lowell and his observatory were largely ostracized. Although the consensus was that some actual features did exist which would account for these markings, in 1909 the sixty-inch

While this idea excited the public, the astronomical community was skeptical. Many astronomers could not see these markings, and few believed that they were as extensive as Lowell claimed. As a result, Lowell and his observatory were largely ostracized. Although the consensus was that some actual features did exist which would account for these markings, in 1909 the sixty-inch Mount Wilson Observatory

The Mount Wilson Observatory (MWO) is an astronomical observatory in Los Angeles County, California, United States. The MWO is located on Mount Wilson, a peak in the San Gabriel Mountains near Pasadena, northeast of Los Angeles.

The observat ...

telescope in Southern California allowed closer observation of the structures Lowell had interpreted as canals, and revealed irregular geological features, probably the result of natural erosion.

The existence of canal-like features was definitively disproved in the 1960s by NASA's Mariner

A sailor, seaman, mariner, or seafarer is a person who works aboard a watercraft as part of its crew, and may work in any one of a number of different fields that are related to the operation and maintenance of a ship.

The profession of the ...

missions. Mariner 4, 6 and 7, and the Mariner 9

Mariner 9 (Mariner Mars '71 / Mariner-I) was a robotic spacecraft that contributed greatly to the exploration of Mars and was part of the NASA Mariner program. Mariner 9 was launched toward Mars on May 30, 1971 from LC-36B at Cape Canaveral Air ...

orbiter (1972), did not capture images of canals but instead showed a cratered Martian surface. Today, the surface markings taken to be canals are regarded as an optical illusion. Psychologist Matthew J. Sharps has argued that perception of the canals by Lowell and others could have been the result of a combination of psychological factors, including individual differences

Differential psychology studies the ways in which individuals differ in their behavior and the processes that underlie it. This is a discipline that develops classifications (taxonomies) of psychological individual differences. This is distingui ...

, Gestalt

Gestalt may refer to:

Psychology

* Gestalt psychology, a school of psychology

* Gestalt therapy, a form of psychotherapy

* Bender Visual-Motor Gestalt Test, an assessment of development disorders

* Gestalt Practice, a practice of self-exploration ...

reconfiguration, and sociocognitive factors.

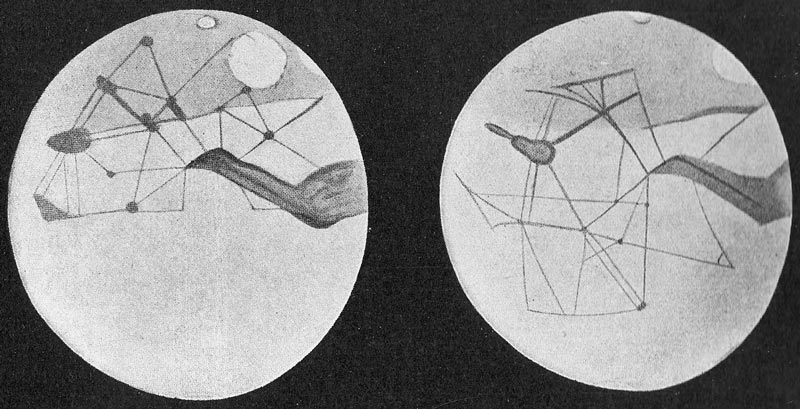

Venus spokes

Although Lowell was better known for his observations of Mars, he also drew maps of the planet

Although Lowell was better known for his observations of Mars, he also drew maps of the planet Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never fa ...

. He began observing Venus in detail in mid-1896 soon after the Alvan Clark & Sons refracting telescope was installed at his new Flagstaff, Arizona observatory. Lowell observed the planet high in the daytime sky with the telescope's lens stopped down to 3 inches in diameter to reduce the effect of the turbulent daytime atmosphere. Lowell observed spoke-like surface features including a central dark spot, contrary to what was suspected then (and known now): that Venus has no surface features visible from Earth, being covered in an atmosphere that is opaque. It has been noted in a 2003 ''Journal for the History of Astronomy'' paper and in an article published in ''Sky and Telescope

''Sky & Telescope'' (''S&T'') is a monthly American magazine covering all aspects of amateur astronomy, including the following:

*current events in astronomy and space exploration;

*events in the amateur astronomy community;

*reviews of astronomic ...

'' in July 2003 that Lowell's stopping down of the telescope created such a small exit pupil

In optics, the exit pupil is a virtual aperture in an optical system. Only rays which pass through this virtual aperture can exit the system. The exit pupil is the image of the aperture stop in the optics that follow it. In a telescope or compou ...

at the eyepiece

An eyepiece, or ocular lens, is a type of lens that is attached to a variety of optical devices such as telescopes and microscopes. It is named because it is usually the lens that is closest to the eye when someone looks through the device. The ...

, it may have become a giant ophthalmoscope

Ophthalmoscopy, also called funduscopy, is a test that allows a health professional to see inside the fundus of the eye and other structures using an ophthalmoscope (or funduscope). It is done as part of an eye examination and may be done as part ...

giving Lowell an image of the shadows of blood vessels cast on the retina

The retina (from la, rete "net") is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then ...

of his own eye.

Pluto

Lowell's greatest contribution to planetary studies came during the last decade of his life, which he devoted to the search forPlanet X

Following the discovery of the planet Neptune in 1846, there was considerable speculation that another planet might exist beyond its orbit. The search began in the mid-19th century and continued at the start of the 20th with Percival Lowell's ...

, a hypothetical planet beyond Neptune. Lowell believed that the planets Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. Its name is a reference to the Greek god of the sky, Uranus (mythology), Uranus (Caelus), who, according to Greek mythology, was the great-grandfather of Ares (Mars (mythology), Mars), grandfather ...

and Neptune

Neptune is the eighth planet from the Sun and the farthest known planet in the Solar System. It is the fourth-largest planet in the Solar System by diameter, the third-most-massive planet, and the densest giant planet. It is 17 times ...

were displaced from their predicted positions by the gravity of the unseen Planet X. Lowell started a search program in 1906. A team of human computers, led by Elizabeth Williams were employed to calculate predicted regions for the proposed planet. The program initially used a camera in aperture. The small field of view of the reflecting telescope rendered the instrument impractical for searching. From 1914 to 1916, a telescope on loan from Sproul Observatory

Sproul Observatory was an astronomical observatory owned and operated by Swarthmore College. It was located in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, United States, and named after William Cameron Sproul, the 27th Governor of Pennsylvania, who graduated ...

was used to search for Planet X. Lowell did not discover Pluto but later Lowell Observatory ( observatory code 690) would photograph Pluto in March and April 1915, without realizing at the time that it was not a star.

In 1930, Clyde Tombaugh

Clyde William Tombaugh (February 4, 1906 January 17, 1997) was an American astronomer. He discovered Pluto in 1930, the first object to be discovered in what would later be identified as the Kuiper belt. At the time of discovery, Pluto was cons ...

, working at the Lowell Observatory, discovered Pluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the Sun. It is the largest ...

near the location expected for Planet X. Partly in recognition of Lowell's efforts, a stylized P-L monogram (♇) – the first two letters of the new planet's name and also Lowell's initials – was chosen as Pluto's astronomical symbol

Astronomical symbols are abstract pictorial symbols used to represent astronomical objects, theoretical constructs and observational events in European astronomy. The earliest forms of these symbols appear in Greek papyrus texts of late antiq ...

. However, it would subsequently emerge that the Planet X theory was mistaken.

Pluto's mass could not be determined until 1978, when its satellite Charon was discovered. This confirmed what had been increasingly suspected: Pluto's gravitational influence on Uranus and Neptune is negligible, certainly not nearly enough to account for the discrepancies in their orbits. In 2006, Pluto was reclassified as a dwarf planet

A dwarf planet is a small planetary-mass object that is in direct orbit of the Sun, smaller than any of the eight classical planets but still a world in its own right. The prototypical dwarf planet is Pluto. The interest of dwarf planets to ...

by the International Astronomical Union

The International Astronomical Union (IAU; french: link=yes, Union astronomique internationale, UAI) is a nongovernmental organisation with the objective of advancing astronomy in all aspects, including promoting astronomical research, outreac ...

.

In addition, it is now known that the discrepancies between the predicted and observed positions of Uranus and Neptune were ''not'' caused by the gravity of an unknown planet. Rather, they were due to an erroneous value for the mass of Neptune. ''Voyager 2

''Voyager 2'' is a space probe launched by NASA on August 20, 1977, to study the outer planets and interstellar space beyond the Sun's heliosphere. As a part of the Voyager program, it was launched 16 days before its twin, '' Voyager 1'', o ...

''s 1989 encounter with Neptune yielded a more accurate value of its mass, and the discrepancies disappear when using this value.

Legacy

Clyde Tombaugh

Clyde William Tombaugh (February 4, 1906 January 17, 1997) was an American astronomer. He discovered Pluto in 1930, the first object to be discovered in what would later be identified as the Kuiper belt. At the time of discovery, Pluto was cons ...

possible. Lowell has been described by other planetary scientist

Planetary science (or more rarely, planetology) is the scientific study of planets (including Earth), celestial bodies (such as moons, asteroids, comets) and planetary systems (in particular those of the Solar System) and the processes of their ...

s as "the most influential popularizer of planetary science in America before Carl Sagan

Carl Edward Sagan (; ; November 9, 1934December 20, 1996) was an American astronomer, planetary scientist, cosmologist, astrophysicist, astrobiologist, author, and science communicator. His best known scientific contribution is research on ext ...

".

While eventually disproved, Lowell's vision of the Martian canals, as an artifact of an ancient civilization making a desperate last effort to survive, significantly influences the development of science fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel unive ...

– starting with H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Lowell Observatory

BBC Science: Percival Lowell

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Lowell, Percival 1855 births 1916 deaths American agnostics American astronomers American pacifists Discoverers of asteroids American people of English descent Harvard College alumni People from Flagstaff, Arizona Businesspeople from Boston Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Pluto Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

The War of the Worlds

''The War of the Worlds'' is a science fiction novel by English author H. G. Wells, first serialised in 1897 by ''Pearson's Magazine'' in the UK and by ''Cosmopolitan (magazine), Cosmopolitan'' magazine in the US. The novel's first appear ...

'', which made the further logical inference that creatures from a dying planet might seek to invade Earth.

The image of the dying Mars and its ancient culture was retained, in numerous versions and variations, in most science fiction works depicting Mars in the first half of the twentieth century (see Mars in fiction

Mars, the fourth planet from the Sun, has appeared as a setting in works of fiction since at least the mid-1600s. It became the most popular celestial object in fiction in the late 1800s as the Moon was evidently lifeless. At the time, the pre ...

). Even when proven to be factually mistaken, the vision of Mars derived from his theories remains enshrined in works that remain in print and widely read as classics of science fiction.

Lowell's influence on science fiction remains strong. The canals figure prominently in '' Red Planet'' by Robert A. Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein (; July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction author, aeronautical engineer, and naval officer. Sometimes called the "dean of science fiction writers", he was among the first to emphasize scientific accu ...

(1949) and ''The Martian Chronicles

''The Martian Chronicles'' is a science fiction fix-up novel, published in 1950, by American writer Ray Bradbury that chronicles the exploration and settlement of Mars, the home of indigenous Martians, by Americans leaving a troubled Earth th ...

'' by Ray Bradbury

Ray Douglas Bradbury (; August 22, 1920June 5, 2012) was an American author and screenwriter. One of the most celebrated 20th-century American writers, he worked in a variety of modes, including fantasy, science fiction, horror, mystery, and r ...

(1950). The canals, and even Lowell's mausoleum, heavily influence ''The Gods of Mars

''The Gods of Mars'' is a science fantasy novel by American writer Edgar Rice Burroughs and the second of Burroughs' Barsoom series. It features the characters of John Carter and Carter's wife Dejah Thoris. It was first published in '' The ...

'' (1918) by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Edgar Rice Burroughs (September 1, 1875 – March 19, 1950) was an American author, best known for his prolific output in the adventure, science fiction, and fantasy genres. Best-known for creating the characters Tarzan and John Carter, he ...

as well as all other books in the Barsoom series.

Asteroid 1886 Lowell, discovered by Henry Giclas

Henry Lee Giclas (December 9, 1910 – April 2, 2007) was an American astronomer and a discoverer of minor planets and comets.

He worked at Lowell Observatory using the blink comparator, and hired Robert Burnham Jr. to work there. He also wo ...

and Robert Schaldach in 1949, as well as crater ''Lowell'' on the Moon, and crater ''Lowell'' on Mars, were named after him. The Lowell Regio

Lowell Regio is a region on the dwarf planet Pluto. It was discovered by the '' New Horizons'' spacecraft in 2015. The region corresponds to the Plutonian northern polar cap. It is named after Percival Lowell who established the observatory where ...

on Pluto was also named in his honor after its discovery by the '' New Horizons'' spacecraft in 2015.

Publications

* ''The Soul of the Far East'' (1888) * '' Noto: An Unexplored Corner of Japan'' (1891) * ''Occult Japan, or the Way of the Gods'' (1894) * ''Collected Writings on Japan and Asia, including Letters to Amy Lowell and Lafcadio Hearn'', 5 vols., Tokyo: Edition Synapse. * * ''Mars'' (1895) * ''Mars and Its Canals'' (1906) * ''Mars As the Abode of Life'' (1908) * ''The Evolution of Worlds'' (1910) (Full text at )See also

*Life on Mars

The possibility of life on Mars is a subject of interest in astrobiology due to the planet's proximity and similarities to Earth. To date, no proof of past or present life has been found on Mars. Cumulative evidence suggests that during the ...

* Noto Peninsula

The Noto Peninsula (能登半島, ''Noto-hantō'') is a peninsula that projects north into the Sea of Japan from the coast of Ishikawa Prefecture in central Honshū, the main island of Japan. The main industries of the peninsula are agricultur ...

* Wrexie Leonard

References

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * *External links

* * * * *Lowell Observatory

BBC Science: Percival Lowell

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Lowell, Percival 1855 births 1916 deaths American agnostics American astronomers American pacifists Discoverers of asteroids American people of English descent Harvard College alumni People from Flagstaff, Arizona Businesspeople from Boston Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Pluto Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters